Tales of Contamination

Contamination occurs through contact, exchange and touch with the Other. It requires contact with the outside, the foreign, the unknown. Like all words, contamination takes on many different meanings and interpretations.

In a book entitled Contagious: Cultures, Carriers and the Outbreak Narrative, written by Professor Priscilla Wald, states that “The word contagion literally means ‘touching together’, and one of its earliest uses in the fourteenth century referred to the circulation of ideas and attitudes. For his part, in his book, Les peaux créatrices, esthétique de la sécrétion, Stéphane Dumas defines contamination as “the penetration of an organism by an intruder who propagates it”. Contamination simultaneously touches us through organic and intellectual matter.

Let us turn to the English anthropologist Tim Ingold and his book Walking with Dragons, published in 2013. Tim Ingold introduces the term interpenetration following his observation of the characteristics of fungi. He comes to “question what we mean by ‘environment’, and ultimately conceive it not as what surrounds – what is ‘out there’ and not ‘in here’ – but as a zone of interpenetration within which our lives and the lives of others intermingle into a homogeneous whole”. In this article, we interpret these zones of interpenetration as entangled spaces, zones of contamination, both intellectual and organic between humans and other species.

The pandemic has exacerbated our fear of contamination and of the Other. Yet, as Marie-Sarah Adenis points out in her article Gloire aux Microbes!, published in the Socialter Revue, “Life is a permanent contamination, the stranger is within us”. In short, contamination is inevitable and this requires proximity, promiscuity, an almost sensual intimacy between humans and micro-organisms such as microbes and fungi.

In the preface to his book Walking with Dragons, Tim Ingold’s reflects on his childhood. The anthropologist’s father was a mycologist, this develops in young Ingold a fascination for mushroom and their entangled ways.

Ingold recalls his fascination as follows :

Mushrooms, you see, just don’t behave like organisms should behave. They flow, they ooze, their boundaries are indefinable; they fill the air with their spores and infiltrate the soil with their sinuosities, their fibres constantly branching and spreading. What we see on the surface of the soil are simply fruiting bodies. But this is also the case with humans. They do not live inside their bodies, as social theorists like to say. Their traces are imprinted on the ground, via their footprints, paths and tracks: their breath mingles with the atmosphere. It remains alive only as long as there is a continuous exchange of materials through layers of skin that are constantly expanding and changing.

Fungi, these mysterious decayers of the living embrace contamination. They defy the notion of boundaries, and therefore of individual identity that humans have forged for themselves.

The contamination is an intimate and continuous intermingling of species and spaces. By bringing mushrooms and human beings together, Ingold questions our relationship to each other and to the world. If mushrooms are not what we imagine, then neither are we. The boundaries of bodies begin to dissolve and dissipate.

As Ingold points out, it is through the exchange between skins, and thus touch, that mutation and change can occur. The human body can be seen as a zone of interpenetration where bacteria and fungi thrive. Re-imagining the world with decayers such as micro-organisms and fungi can perhaps help us to transcend the individual identity.

In her article, Marie-Sarah Adenis states : “An intimate and deep pact unites us. Microbes weave invisible networks that link the living to each other, in life and in death. They are our ancestors and our contemporaries, our relatives and our cousins. They are inside us, living in intimate territories, deep inside us, even in our cells, and are active night and day, without respite, making us plural beings, overflowing identities, half-human and half-microbial.” . We are plural, the individual fades away to reveal a porosity, an unconditional promiscuity between our bodies and the decayers of the living. This plurality of being invokes a certain tenderness and a form of sensuality between humans and decayers.

In 2012, the Austrian artist Sonja Baumel unveiled the performance/installation art piece titled Expanded Self in collaboration with the biologist Erich Schopf. Baumel’s practice transcends the limits of the individual and explores the intimate relationship we share with the Other. This particular work is a giant petri dish, measuring 210 x 80 cm, filled with a gelatinous substance, a nutritive medium for bacteria, called agar. The artist lies her naked body in this petri dish and deposits the imprint of the microscopic bacteria and fungi that inhabit her skin. On her website, Sonja Baumel explains that the work is “the living and growing image of a body”. As the work progresses, the invisible population slowly reveals itself to the viewer. The artist explains that Expanded Self is an “imprint of a human body [that] is a kind of metaphor for new perspectives on our person.” . These living imprints, revealed through contamination, unfold new ways of perceiving the living world. We may interpret the piece Expanded Self as a Cultured Medium, where the intimate and intermingled membranes of humans and microscopic Others are revealed.

The existing intimacy between humans and decayers is also explored by artist and researcher Tarsh Bates in her article ‘Human Thursh Entanglements: Homo Sapiens multispecies ecology’, written in 2013. Candida albicans, is a single-celled fungus that is symbiotic, i.e. co-existing, with humans. These microscopic organisms “make up the intestinal and urogenital flora of humans; without them, we would have difficulty digesting because they break down the sugars in our blood”. Candida albicans is the subject and medium of Tarsh Bates’ research. We know Candida better by the gentle name of vaginal mycosis or candidiasis. Indeed, Bates points out that ‘many women have intimate, embodied and emotional relationships with the microscopic creature, which usually involves trying to kill it’. Despite its invasiveness, Tarsh Bates does not see Candida as a nuisance but rather as an inspiration to see new creative possibilities in our changing world.

In her article, Bates goes on to say, “The power relationship between Homo and Candida is complex: a Candida infection has no animosity. Driven by its environment, us, it reacts to the amount of sugars in the bloodstream, to the other bacteria in its ecology, to the surface to which it adheres”, Candida contamination is certainly unpleasant, but not deliberate. Our bodies are simply the culture media for Candida.

The palpable promiscuity between Candida and Homo Sapiens invokes a dimension of tenderness belonging to the one of Care. In her article, Bates describes her intimate relationship with the single-celled organism she cultivates. She states, “I am very conscious of my relationship with this seemingly harmless organism and feel a certain tenderness for the smooth, shiny cream of the colonies. By growing her own cultures and caring for Candida albicans, Tarsh Bates develops a real empathy, a compassion, a cross-species intimacy with her microscopic Others.

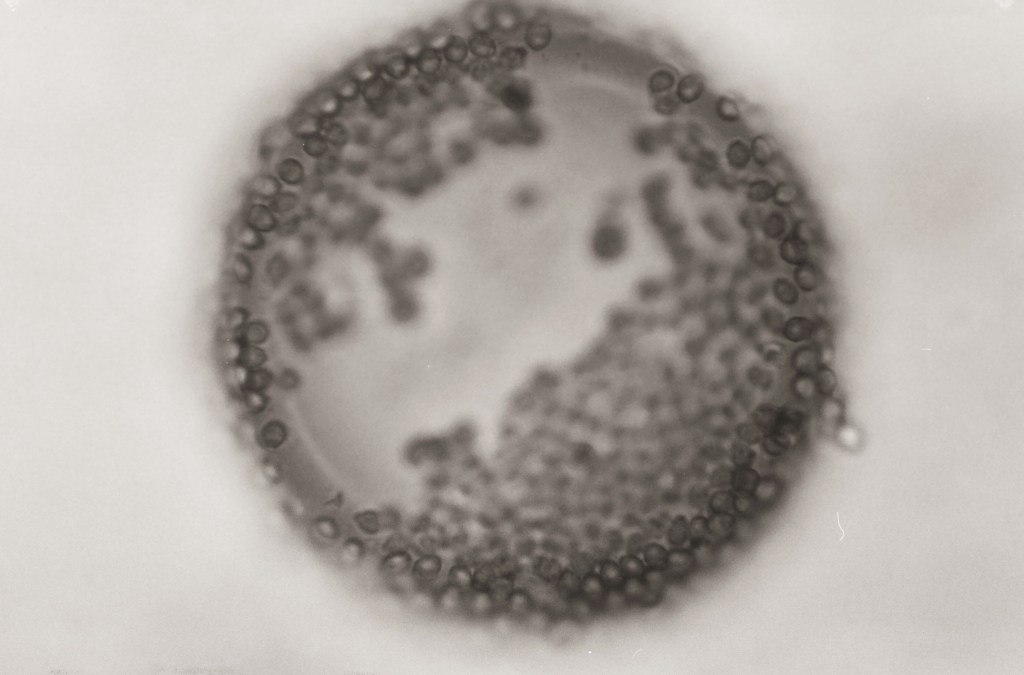

In an attempt to pursue the intimate relationship between human and microscopic Other, we in turn, have created a work entitled On the edge of skin (2022). Echoing Sonja Baumel’s and Tarsh Bates’ works and research, we made three glass petri dishes with a nutrient medium to cultivate micro-organisms.

These dishes are of increasing size, the three copies measuring respectively circa. 15cm, circa. 20cm and circa. 25cm respectively. The lids are made of clear glass, so that the viewer may lean over and observe the interior. The containers are dark blue to create a contrast between the bottom of the petri dishes and the bacterial population. Laboratory petri dishes, long made out of glass, are now being replaced by disposable plastic models. The use of glass thus creates an echo with the craft of glass blowing for laboratories.

Emma Carter Millet & Thomas Clerc, On the edge of skin, (glass, agar, bacteria) 3 samples, circa. 15cm, circa. 20cm and circa. 25cm. 2022.

Depending on its composition, the nutrient medium can be used to cultivate bacteria, fungi and other micro-organisms of interest. The work On the edge of skin (2022) is an interactive and performative work culture medium for the bacteria that inhabit our skins, it is a medium where intimately intermingled membranes are revealed. Once the agar nutrient medium has been poured into the petri dishes, the spectators are invited to contaminate the works by depositing their microbial prints. The spectators, now actors of the piece, contaminate the culture medium with their own micro-organisms.

Emma Carter Millet & Thomas Clerc, On the edge of skin, (glass, agar, bacteria) 3 samples, circa. 15cm, circa. 20cm and circa. 25cm. 2022.

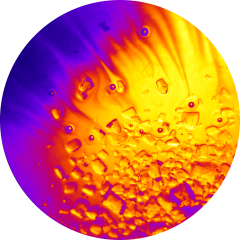

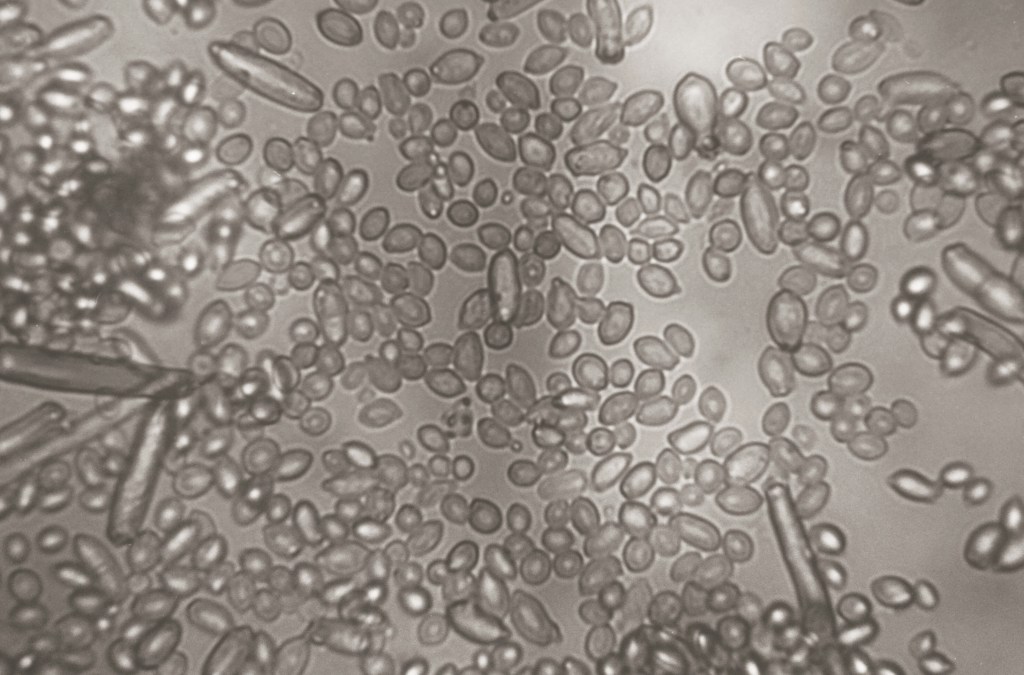

This culture medium cultivates a skin to skin, membrane to membrane relationship, which in turn generates what Anna Tsing would name a tale of contamination . After a week, the colonies of microorganisms become visible to the naked eye. These colonies reveal colours and draw shapes and textures worthy of the most beautiful paintings.

The pandemic has exacerbated our fear of the invisible living and of contamination. Although, only a tiny fraction of viruses are harmful to humans. The fear of invisible life is palpable, however, with the development of interactive petri dishes, fear can be transformed into curiosity. Once the bacterial population is sufficiently developed, we observe the invisible bacteria and fungi under the microscope. Then the microbial landscapes that are revealed under the lens are photographed with a film camera. These photographs document the interactive living performance, invite wonder and a deeper understanding of interspecies intimacy. On the edge of skin (2022) allows us to intertwine bodies and imaginations with the microscopic Others.

Sampled bacteria populations from On the edge of skin (2022), microscope x 1000, Seen on an adapted OM 10 Canon Film Camera, Printed, Taken by Thomas Clerc, 2022.

References

Tarsh, Bates, « HumanThrush Entanglements: Homo Sapiens as a Multi-species Ecology »PAN (Melbourne, Vic.) 10, 2013.

Tim, Ingold, Marcher avec les dragons, Bruxelles, Zones Sensibles Éditons, 2013.

Sonja, Baumel, Expanded Self, Publié en 2012, [Consultation le 10 Février 2022] Disponible sur : < https://sonjabaeumel.at/work/expanded+self/>

Priscilla, Wald, Contagious: Cultures, Carriers and the Outbreak Narrative, Duke University Press, 2008.

Stéphane, Dumas, “Les peaux créatrices, esthétique de la sécrétion”, Paris, Collection d’esthétique Séries, #81 Les Belles Lettres, 2014.

Anna L, Tsing, Le Champignons à la fin du monde ; Sur les possibilités de vivre dans les ruines du capitalisme, Traduit par Philippe Pignarre, Paris, Les Empêcheurs de Penser en Rond, 2017.

Marie-Sarah, Adenis, « Gloire aux Microbes ! », (Dir.) Baptiste Morizot, Hors-série, Socialter, publié en décembre 2020 [Consultation le 10 décembre 2021]

This website and the works by Emma Carter Millet & Thomas Clerc are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.