Agrobiochemistry :

The Core Elements

Biochemistry

Every organism on Earth is made out of atoms. Atoms can bind together, forming molecules. The main atoms in living beings are Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H) & Oxygen (O). They are the building blocks of the essential biological molecule families : carbohydrates, lipids, nucleic acids (DNA), and proteins.

Let us consider a photosynthetic being, such as a tree, with plenty of carbon dioxide (CO2), water (H2O) and light. Using light as a power supply, the photosynthesis reaction may combine CO2 and water to form glucose (C6H12O6) and dioxygen (O2) :

6 x CO2 + 6 x H20 —> C6H12O6 + 6 x O2

Therefore in the right conditions (accessible water, CO2 and light), an organism capable of photosynthesis has a virtually unlimited supply of C, H & O.

Vital cellular structures such as DNA, proteins and cell membranes require other atoms for their construction. The most important are :

– Nitrogen (N) : for DNA & proteins

– Phosphorous (P) : for DNA, cell membranes & Energy management

– Sulfur (S) : for proteins

These compose the main bricks of life, the CHONPS.

Plants also love potassium (K, from the latin word kalium) as they need it for protein production and to operate their leaves.

As a general rule, we can keep in mind that plants crave N, P & K. This is why a common fertilizer bag will have NPK written on it, along side with a label of the percentage by weight of these nutrients. As a plant is growing, the atoms limiting the growth are N, P & K. This means that artificially adding these can directly increase the speed of growth.

Now, without these essential atoms, an environment cannot host life as we know it. Luckily, our atmosphere contains and transports C, H, O & N everywhere. As P, S & K are lacking from our atmosphere, plants will need to find them in soil. Nitrogen composes 78% of the atmosphere. It is flying around under the triple bonded form of N2 (N

Nitrogen

Amazingly -and because it is such a valuable resource- bacteria and plants have evolved to form symbiotic relationships in order to extract this atmospheric nitrogen. The plant hosts and feeds underground bacteria which break this triple bond and trade the valuable nitrogen in an assimilable form. The two nitrogen-fixing associations are :

– Actinorhizal (Rosales, Fagales & Cucurbitales plants & Frankia bacterias) concerns trees and shrubs, including the alder trees.

– Rhizobial (Fabaceae plants & Rhizobium bacterias) are the beans we know and love. They are protein-rich thanks to the nitrogen supply. It includes legumes such as beans, soybean, peas and many more !

Rhizobial symbiosis take place in root nodules such as these.

Adapted from Ninjatacoshell’s work, CC BY-SA

These collaborations are used as a way to fertilize lands with nitrogen. This happens through nitrogen-rich leaves falling to the ground in autumn, stems being decomposed or through fine roots dying underground, releasing nitrogen back in the soil.

Adding legumes in a crop rotation is one way to add nitrogen to the soil before growing cereal. Many crop rotations, such as the Norfolk four-course system invented in the early 16th century, fully take leverage on these effects and never leave the soil barren, thus giving a high yield of cereals, fodder and grazing without exposing soil organisms to UV light.

Phosphorous

Phosphorous cannot be extracted from the atmosphere, so it has to be extracted from soil. Luckily, it is pretty much in every type of soils. Unluckily, it is present in small amounts. It has to be mined and concentrated from rocks or harvested from decomposing matter. In 70-80% of land plant species, this operation is outsourced to Arbuscular Mycorhizzal Fungi (AMF)1.

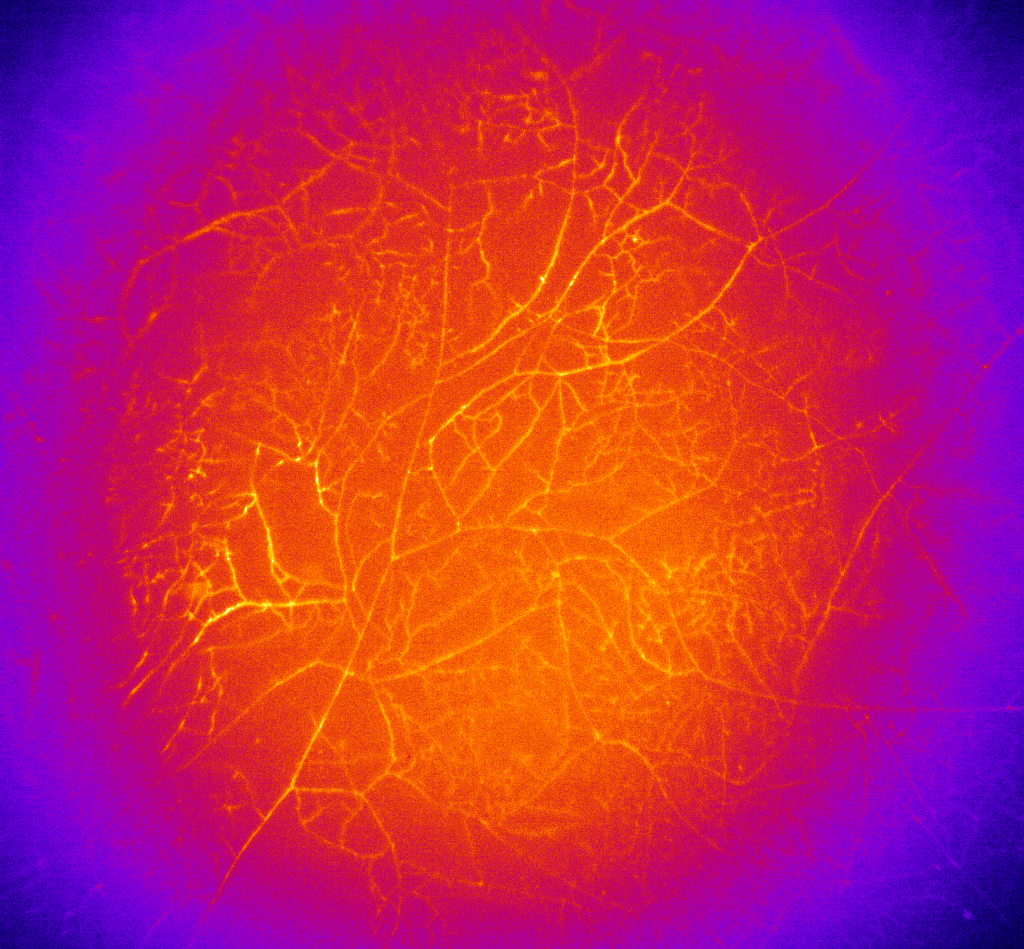

This is another incredible symbiosis, now involving a plant and a fungus (Glomeromycota). The fine fungus enters the plant’s root cells and forms intimate tree-like structures called arbuscules that increase the contact-surface between the two beings. This is reminiscent of a small marketplace, where the plant exchanges lipids and sugars (energy-rich carbon sources) for mined phosphorous. The importance of this exchange for plants is highlighted by its widespread incidence and the energy provided to the AMFs, corresponding to 4-20% of the plant’s photosynthesis products2.

Mycelium of Rhizophagus irregularis, a commonly studied AMF, colorized

Thanks to the AMF extended network, the mycelium, these beings are amazing at finding, mining and transporting phosphorous from soil particles all the way to plant roots. The AMF symbiosis is ancient, at least 400 million years old3. It is so old that it preceded roots and is believed to have helped plants first colonize the land. Its impact on plant growth is such, that it is believed to have induced a climate change during the Paleozoic Era (~ 539 – 252 million years ago). This was achieved by a 10-fold reduction in atmospheric CO2 levels due to enhanced plant growth and size4.

The AMF association has many other observed advantages, including resistance to drought and improved soil structure. Yet today, in a time of impeding droughts and unpredictable weather caused by climate change, industrial agricultural practices are working against these beings. The damage is caused by tillage, fungicides and inorganic fertilizers. Tillage disrupts the mycelium network, fungicides obviously kill Fungi and inorganic fertilizers reduce the need for the AMF symbiosis.

As we want our agriculture to produce high yields, we sprinkle ready-to-use phosphorous on fields. These phosphorous fertilizers are extracted through human mining operations, which are energy intensive and have dreadful socio-environmental impact.

Phosphorous deposits are unequaly distributed across countries : Norway potentially holds 50% of the world known reserves, Morocco and the Western Sahara territory holding 35%. Phosphorous fertilizers use ~90% of the mining outputs5.

Potassium

Potassium is present inside all living cells as an essential ion (K+). Indeed, it is estimated that managing this ion around our cells represents 20% of our daily intake of energy6.

A simple source of potassium is potash.

Potash is made by mixing a volume of wood ashes with a volume of water, stirred well, we recover only the liquid solution and boil it down until all water has evaporated. We would be left with potassium carbonate crystals. Prior to the Industrial Era, this was the main way to concentrate potassium.

Today, most of our potassium comes from mined minerals. These mines used to be ancient inland oceans. After the water evaporated, the potassium salts crystallized into beds of potassium ore.

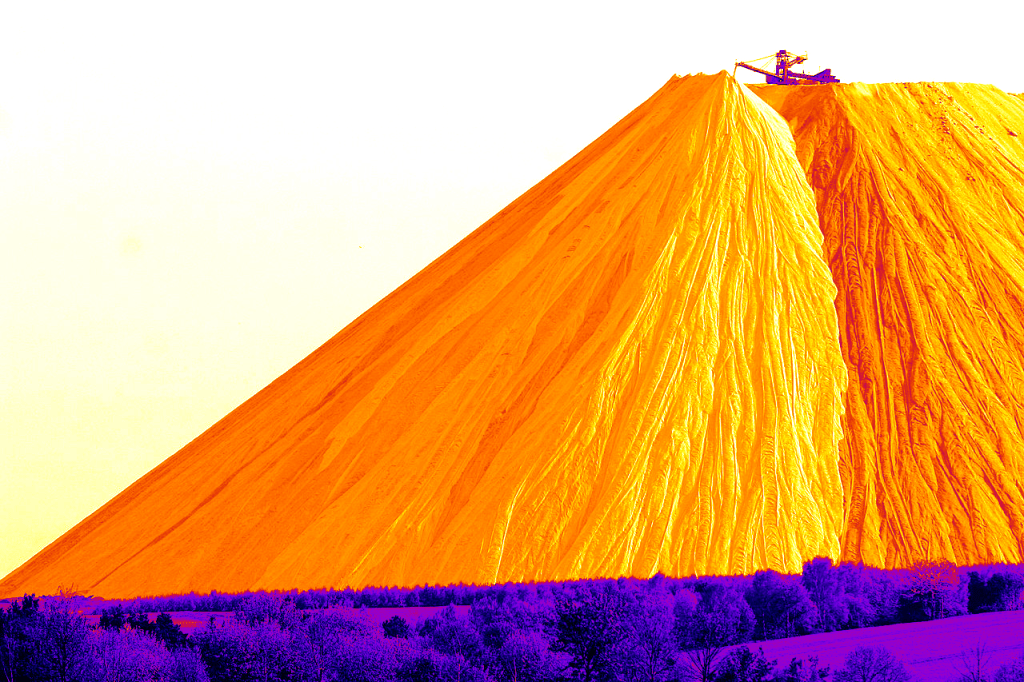

When we extract this ore, we also extract a lot of table salt (sodium chloride – NaCl) as a byproduct. One way to deal with it is to dump it next to the mine. This is happening in Heringen, Germany :

The ‘Monte Kali’, a mountain mainly composed of table salt disposed as a waste from the potassium mine of Heringen, Germany.

Adapted from Armin Kübelbeck’s work, CC BY-SA

Dumping salt in the environment has side effects. The neighbouring Werra river as well as groundwater has become salty because of this industry. The invertebrate fauna was reduced drastically. Yet the K+S company is licensed to keep dumping salt at the facility until 2030. Fertilizer production uses 93% of the potassium mining outputs7.

Another good source of potassium is urine.

An average human pee contains 7g of potassium & 5.6g of nitrogen. This comes from the food we eat, therefore from the fields. By physically displacing these elements to cities and dumping them in waste waters, we create a negative flux depleting the fields. Mining these elements to balance this flux is a short-term solution. Another way to solve this negative flux is to put our excreta back into the fields to close the cycles.

In a future article, we’ll investigate these atom cycles and how they are keys to rebuild and re-imagine our society.

References

[1] Sally E. Smith, David Read, Editor(s): Sally E. Smith, David Read, Mycorrhizal Symbiosis (Third Edition), Academic Press, 2008, Pages 1-9,

ISBN 9780123705266, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012370526-6.50002-7

[2] Berta Bago, Philip E. Pfeffer and Yair Shachar-Hill, Carbon Metabolism and Transport in Arbuscular Mycorrhizas, Plant Physiology, Volume 124, Issue 3, November 2000, Pages 949–958, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.124.3.949

[3] Brundrett, M.C. (2002), Coevolution of roots and mycorrhizas of land plants. New Phytologist, 154: 275-304. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00397.x

[4] Mills Benjamin J. W., Batterman Sarah A. and Field Katie J. (2018), Nutrient acquisition by symbiotic fungi governs Palaeozoic climate transitionPhil. Trans. R. Soc. B3732016050320160503http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0503

[5] Stephen M. Jasinski, “Phosphate Rock”. US Geological Survey, Minerals Yearbook, 2013.

[6] L.P. Milligan, B.W. McBride, Energy Costs of Ion Pumping by Animal Tissues, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 115, Issue 10,

1985, Pages 1374-1382, ISSN 0022-3166, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/115.10.1374.

[7] Ober, Joyce A. “Mineral Yearbook 2006:Potash” (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-11-20.