Fromage de chèvre

Goats are estimated to be the first species to be domesticated. Our common history might be 10 000 years old.1 It is therefore logic to think that the first human-made cheeses were done with goat (and sheep) milk -at least- 7 500 years ago.

Since 2014, there is more than 1 billion goats in the world. More than 200 million of them are producing milk.2 More than 120 000 tonnes of goat cheese were produced in 2020 in France.3

Having had the chance to work in a goat farm for a few weeks, we wanted to share this goat cheese guide. All you are going to need is a few goats, bit of land and various farming utensils.

The goats

Food & drinks

Goats can pasture in open fields without problem. They are not picky eaters and are usually robust fellas. You can count three to nine goats per hectare, depending on the parcel’s productivity.

In the stables, they enjoy hay and a diversified mixture of dried cereals and herbs (barley, dehydrated alfalfa, maize, ground soy, etc.) as well as a salt rock dispensers.

Drink-wise, they should have unlimited access to water and will drink plenty when coming back from the fields.

Gourmet goats, however, like a bit of fermented whey in their drink. Whey is the by-product of cheese-making, the liquid found on top of yogurts. When milking goats for cheese, we need them so stay hydrated. They find delicious this flavoured protein-rich acidic drink and it will help them drink good amounts. Whey contains minerals such as calcium and phosphorous. These minerals also help process the milk into cheese.

Milking the goats

The productive alpine goat can produce up to 850L per year. Goats can be milked once or twice a day, with dual milking producing more milk.

Cheese making

Curdling

Fresh warm raw milk should be mixed with whey and fungal spores as soon as possible.

Use approximately 100mL of whey per 20L of milk. The acidic and mineral-rich fermented whey will bring lactic acid bacteria (LABs) to the cheese. If needed, whey can be stored in the fridge for a few days.

For the fungal spores, you can use a pinch of Geotrichum candidum, a fungus that probably already inhabits your gut and skin. It is common in many french cheeses and nordic yogurts.

Leave the whole container covered in a clean, cold & dark room for an hour.

An hour has passed, it is time to add rennet. As rennet may not be the most humane way to make cheese nowadays, we can use commercially available Chymosin (rennet’s main enzyme) produced by microbes in bio-reactors. One drop of rennet per liter of milk is good for this recipe, but hard cheese, for example, uses more rennet. Manufacturers usually provide an optimal dosage for various recipes.

Various plant extracts, containing the right proteases, may also work. Fig juice is suggested in Homer’s Illiad. Any edible acid can also work, although giving a softer curd.

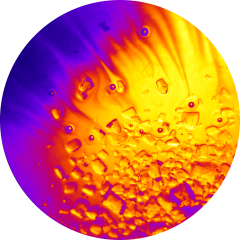

Leave the whole thing covered and undisturbed for 12 hours (summer) or 24 hours (winter). You should get a firm curd floating on top of the liquid whey.

The curdling process works best in acidic solution containing calcium and phosphorous, which is why fermented whey is so convenient.

Curd processing

If the curd is deemed too fluid, we can pre-drain it in a clean muslin cloth for about 6 hours. If it is too hard, water can be added.

Next, we add salt to the curd (1-2g salt / 100g curd) and mix thoroughly.

We’ll then use a ladle to transfer the mix into small strainers called faisselles. These strainers will determine the final shape of our cheese and comes in many forms (pyramide, log, bricks, etc.) so you can be creative !

The curd in strainers should be placed in a cold dry room and left to strain for 12 hours. The best option is to put them onto a clean collecting table/container that collects all the runoff whey.

We then carefully take out the cheese out of the faiselles, flip them and put them back for 12h.

Once they are strained, carefully tip the cheeses out of their little strainers and place them on drying racks.

Drying & Maturing

The cheese can stay at room temperature (80-85%RH – Relative Humidity) for a day in order for the fungi to colonize the cheese’s surface.

They should be then put in a cool (11-13°C) and somewhat dry room for them to dry for a few days. They should loose some weight (~20%) during this process.

Then is time for the proper maturing -or affinage– to happen. The cave should be cool (8-13°C) and humid (80-95%RH). A higher humidity (95%RH) will give soft and runny cheeses whereas a dryer room will give hard and strong cheeses. They can be left from 4 to 60 days.

While ripening, the cheeses should be frequently turned upside down. A more frequent turning over should give a more homogenous cheese surface.

Final comment

As you can see, cheese-making is a lengthy and precise process requiring experience and patience. We hope that this guide will make you appreciate -even more- the fabulous food that is cheese and the efforts that went into producing it.

A complete spec sheet for lactic cheese production is available here in French

References

[1] Y. Hatziminaoglou, J. Boyazoglu, The goat in ancient civilisations: from the Fertile Crescent to the Aegean Sea, Small Ruminant Research, Volume 51, Issue 2, 2004, Pages 123-129, ISSN 0921-4488, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2003.08.006.

[2] https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home

[3] https://www.fromagesdechevre.com/chiffres-cles/